by Professor Eamon Harper

The George Gamow portrait is by William C. Parke, who explains: "The ALA is the amino-acid nickname (for alanine) Gamow selected in the RNA Tie Club he started with 20 members (one for each amino acid), including Watson, Crick, and Feynman. The helix represents DNA. Gamow is wearing a GW robe. The background shows the Spring 2000 'BOOMERANG project' image of the variation in microwave radiation left over from the big-bang explosion about 15 billion years ago.

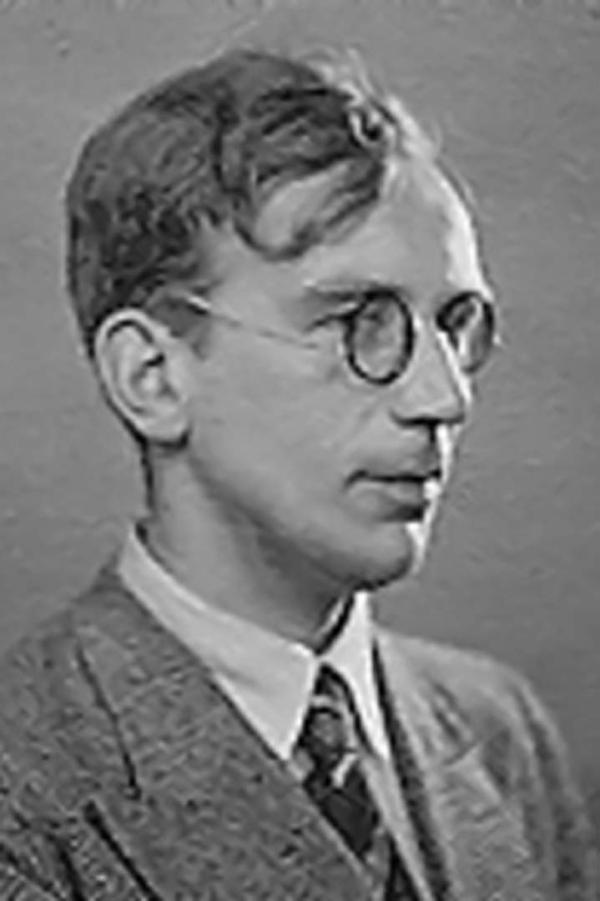

In August 1934 there appeared on the GW campus a 6-foot-3-inch, 30-year-old, flaxen-haired, Ukrainian émigré scientist. His startlingly blue eyes twinkled myopically behind lenses that resembled the bottoms of cider bottles. He conversed with a cosmopolitan circle of friends in a variety of European languages, with a fractured but poetic delivery that was animated and usually high-pitched. His name: George Gamow [pronounced GAM-off].

Gamow had already made quite a name for himself among physicists in Europe, but not many in the United States knew much about him in 1934. Few could have predicted that he would achieve worldwide renown as an astrophysicist and as the chief proponent of a bizarre theory of cosmic evolution called the "big bang," a schema that today is the subject of intense theoretical and observational research. Over the next 22 years, the ebullient and charismatic Gamow-"Geo" to most of his colleagues-left an ineradicable impression, both at the University and throughout the nation. Soon after his arrival in Washington, he instituted a series of conferences in theoretical physics and related areas. Conference topics ranged from nuclear physics to cosmology to biological genetics. Some of the greatest minds of the time-including Hans Bethe, Niels Bohr, Paul Dirac, Enrico Fermi, Robert Oppenheimer, Edward Teller, and John von Neumann-were frequent participants. Never had GW witnessed such a concentration of intellect as during the balmy mid-April days when Gamow usually scheduled his annual "witches Sabbath" in the nation's capital.

In addition to developing the big bang theory of the expanding universe, Gamow made enormous contributions to the understanding of the nucleus of the atom, the activity of stars, the creation of the elements, and the genetic code of life.

He also laid the foundation for the theory of thermonuclear reactions, and his formula describing the temperature dependence of fusion reactions has been a cornerstone of thermonuclear bomb and reactor work. One of the observing scientists at the "Mike" H-bomb test on Bikini atoll in the Pacific in 1949, he was described by the United Press International reporter covering the event as "the only scientist in America with a real sense of humor." The Associated Press man on the scene said, "I get a kick out of calling him. He can always take the most technical information and make it simple."

He delighted lay readers with several books featuring the timid but inquisitive fictional bank clerk C. G. H. Tompkins. Many now-famous scientists (Nobel laureates Francis Crick and Robert Wilson come to mind) have cited the Tompkins series, or other of Gamow's popular gems (such as One, Two, Three ... Infinity), as having stimulated their youthful fascination with science. In 1956, the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization awarded him the Kalinga Prize for the popularization of science.

Gyorgy Antonovich Gamow was born in Odessa, Ukraine, in 1904. His love of science manifested itself early. Astronomy, for example, captivated him after his father gave him a small telescope for his 13th birthday.

George Gamow looking toward the future in Odessa, summer 1907

In 1921-22 he studied at Odessa's Novorossiya University and from 1922 to 1928 took classes at the University of Leningrad. In 1928, he attended summer school in Göttingen, Germany, at that time the hotbed of the new quantum theory. There he succeeded in explaining nuclear radioactivity as a quantum-mechanical phenomenon.

That insight explained experimental findings of scientists at the Cavendish Laboratory in Cambridge, England, led by the titan of nuclear physics, Ernest Rutherford. Gamow went on to apply quantum mechanics to a general theory of low-energy nuclear reactions, essentially founding that field of study.

The significance of his work was apparent to Niels Bohr, who was to theoretical physics what Rutherford was to experimental physics. Bohr offered Gamow a 1928-29 fellowship at the Theoretical Physics Institute of the University of Copenhagen. There Gamow invented what was to become known as the liquid-drop model of the nucleus. Later, Bohr and the American theorist John A. Wheeler used the model to explain the phenomenon of nuclear fission.

While at Bohr's institute, Gamow collaborated with the Austrian physicist Fritz Houtermans and the English astrophysicist Robert Atkinson on the first calculation of stellar thermonuclear reactions. That theory rested largely on Gamow's earlier insights into the mechanism of nuclear reactions and some years later showed the way for Carl von Weizäcker, Hans Bethe, and Gamow's GW student Charles Critchfield to provide the correct theory of thermonuclear energy generation in stars.

At Bohr's urging, Gamow spent 1929-30 as a Rockefeller Fellow at Cambridge University, home to Ernest Rutherford and his collaborators at the Cavendish Laboratory.

The young Ukrainian had a straightforward, no-nonsense way of doing theoretical physics. His approach was strongly intuitive and he lost little time on florid mathematical formalism. That outlook commended itself to the redoubtable Rutherford, who was, to put it mildly, skeptical of the value, if not of all theoretical speculation, certainly of many theoretical scientists.

Gamow succeeded in demonstrating to Rutherford the viability of a proposal-advanced by John Cockcroft and Ernest Walton, two of Rutherford's young co-workers-to build a proton accelerator in order to study the atomic nucleus. Thus Gamow played a major role in the theoretical aspects of the 1932 experiment in which Cockcroft and Walton split the lithium-7 nucleus into two alpha particles by bombarding it with high-energy protons. (That accomplishment won wide-spread attention when presented in a 1932 paper. Einstein said in The New York Times that the results provided the strongest evidence yet adduced for the equivalence of mass and energy.)

John Cockcroft and George Gamow at Cavendish Laboratory, 1931

In sum, Gamow had established himself as one of the leaders in the rapidly expanding field of nuclear physics before his 25th birthday.

Many intellectuals fled Europe as communist and fascist oppression intensified during the 1930s. Gamow, who became a professor at the University of Leningrad, was one of the first.

His posthumously published autobiography, My World Line, contains vivid accounts of some of his attempts to escape from the Soviet Union. In what he describes as the "Crimean campaign" of 1932, he and his new wife, Lyubov Vokhminzeva, nicknamed "Rho," tried to cross the Black Sea to Turkey. Gamow had put the distance at about 170 miles. The voyage was to be made in a small kayak equipped only with paddles and provided with little more than eggs, chocolate, strawberries, and two bottles of good brandy.

"The first day was a complete success..." he writes. "I'll never forget the sight of a porpoise seen through a wave illuminated by the sun sinking below the horizon." In less than 36 hours, however, the weather turned: "The force of the wind pressing against my chest was moving the boat backward, stem first."

The intrepid but exhausted pair had to return to shore. After a couple of days in a hospital, Gamow managed to persuade Soviet authorities that the unexpectedly inclement conditions had supervened to spoil the boat's sea trials!

On their return to Leningrad from a later and equally unsuccessful attempt to escape, Gamow and Rho were more than a little surprised to find that the government had appointed him to represent the Soviet Union at the upcoming Solvay theoretical physics conference to be held in Brussels in October 1933. George resolved to take advantage of this opportunity to leave the Soviet Union for good. He used his acquaintance with Soviet science minister Nikolai Bukharin to get an interview with Stalin's right-hand man, the dour and hard-headed Vyacheslav Molotov, in which he secured the latter's approval to allow Rho to accompany him to Brussels.

After the conference, Gamow accepted an invitation to lecture at the University of Michigan Summer School in Theoretical Physics. During that summer of 1934, GW President Cloyd Heck Marvin and Merle Tuve (director of the accelerator laboratory at the Carnegie Institution of Washington) invited Gamow to come to Washington. He would conduct research at Carnegie and join the University's physics department.

Gamow advanced three conditions. First, he wanted to invite a colleague of his choice to join the GW faculty to work with him. The man he had in mind, Edward Teller, then at Birkbeck College in London, was appointed to the GW physics department a year later. Second, he asked for Marvin and Tuve's support in organizing a conference on theoretical physics to be held annually in Washington under the joint auspices of the University and the Carnegie Institution. Third, he requested that his initial appointment at GW be described as visiting professor. (Since his Soviet passport allowed him to remain legally outside the Soviet Union for only a year, he wanted to give the impression that he might not be contemplating defection.)

Five years later, Gamow became a naturalized U.S. citizen. During World War II, while still teaching at GW, he worked as a consultant for the U. S. Navy. After the war, he taught a course in nuclear physics to naval officers, with Admiral Chester Nimitz among his students. The military-and private industry-frequently called on his expertise.

Throughout his long GW career, Gamow pursued eclectic scientific interests. Abstract mathematics, the workings of turbine and internal combustion engines, astrophysics, the chemical and biological complexity of matter, the properties and structure of the interior of our planet, and the application of the theories of relativity and quantum mechanics to natural phenomena immense and subatomic-all those excited his insatiable curiosity. The mathematician Stanislaw Ulam. said that Gamow demonstrated, "among other outstanding traits, perhaps the last example of amateurism in scientific work on a grand scale."

Gamow disliked working in crowded fields of research, even if it was an area he himself had developed, or one in which he had acquired prestige and eminence. Not long after coming to GW, he shifted from purely nuclear physics to astrophysics and the application of his discoveries in nuclear physics to the problems of stellar birth, evolution, and energy generation-especially the internal structure of red giant stars. That, in turn, led him to the study of galaxy formation and the question of the creation of the elements and to evolutionary cosmology in general. His findings laid much of the foundation for our present understanding of those phenomena.

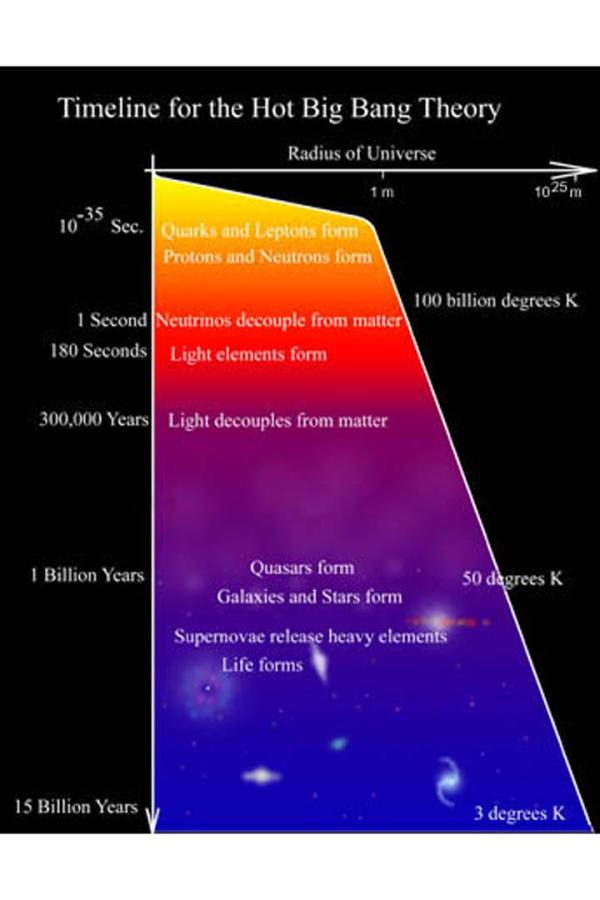

However, he is best remembered for his work on nucleocosmogenesis (the process by which the elements are created out of more fundamental components) and the development of the physical theory of the big bang model of the universe, as well as for his part in the prediction of the existence of cosmic background radiation.

Gamow, his former student at GW, Ralph Alpher, and their long-time colleague Robert Herman were the first to systematically develop the physical aspects of the cosmological theories of the Russian mathematician Alexander Friedmann and the Belgian cosmologist George Lemaitre. The work of Gamow, Alpher, and Herman placed Friedmann's and Lemaitre's conception of the universe on a material (and thus physically observable) foundation. Friedmann and Lemaitre independently had originated the idea that the universe might have had a beginning, which could be represented mathematically as a singularity of Einstein's equations of general relativity. The first announcement of the consequences of Gamow and Alpher's development of the big bang theory of the early universe came in "The Origin of Chemical Elements" (Physical Review, April 1, 1948), one of the most celebrated papers in modem scientific literature.

In a paper published in the British journal Nature later in 1948, Gamow developed equations for the mass and radius of a primordial galaxy (which typically contains about one hundred billion stars, each with a mass comparable with that of the sun). Amazingly, his equations contained only fundamental parameters such as Newton's gravitational constant, Planck's constant, the charge and entropy quanta, and the binding energy of the deuteron!

For its time, that proposed connection between microscopic quantities and cosmic behavior was audacious in the extreme. Today such unbridled speculation has become, if not commonplace, at least not rare in the pages of highly respected scientific journals. Depending on how one views the license that such modem luminaries as Stephen Hawking allow themselves in their cosmological speculations (wormholes, quantum foam, etc.), one might either blame or acclaim George Gamow for leading the way in the early '50s, when it was downright dangerous to one's academic reputation to act so adventurously.

Gamow had often dealt with biological matters in his popular writings. Many of his friends-such as Max Delbrück and Albert Szent-Gyorgy, both of whom were to win the Nobel Prize-were biologists of distinction. Nonetheless, Gamow's abrupt and precipitous plunge into the theory of genetic coding in 1953 surprised even his closest friends by its daring originality. In mid-1953, having read the famous paper by Francis Crick and James Watson describing the double helical structure of DNA, Gamow sent Crick a letter, in which he outlined a mathematical code connecting the structure of DNA with the existence of 20 amino acids. The latter are the building blocks of the proteins that form the most important constituent of all biological organisms.

Gamow explaining a point of interest to members of the Junior Academy of Scientists at GW Lisner Auditorium, 1952

Crick and Watson did a lot of their brainstorming in the Eagle pub in Ben'et Street in Cambridge, hard by the Cavendish Laboratory where they carried out their genetic researches. It was within the walls of those hallowed precincts that Crick showed Watson the Gamow letter.

Gamow's coding proposal hit the biological genetics community like a thunderbolt. His great innovation was the introduction of mathematical reasoning to the coding problem without dwelling too much on biochemical details. Soon the biological world roiled with feverish activity directed toward abstract mathematical attempts to unravel the genetic code. Gamow and Crick were in the van of the enterprise.

In the end it was two experimental biologists, Marshall Nirenberg and J. Heinrich Matthaei, who cracked the code in their laboratory at the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Md. No mathematical regularity of the kind Gamow contemplated has been discerned between the structure of the DNA and that of the amino acid sequence in proteins.

Nevertheless, his astounding insight into the nature of the question to be posed played a significant part in stimulating the enormous advances that have occurred in biological genetics and in the understanding of the essentials of genetic coding since 1953. Those achievements are all the more remarkable for having being inspired, not by a trained biologist, but by a practicing physicist and cosmologist.

Gamow left GW in 1956 for the University of Colorado at Boulder, where he continued working until his death in 1968. But his impact on GW endures, and this spring we unveiled a campus memorial to him. A bronze plaque on a granite boulder details the scientific and literary accomplishments of the man whom his good friend Edward Teller described as follows:

"Gamow was fantastic in his ideas. He was right, he was wrong. More often wrong than right. Always interesting; ... and when his idea was not wrong it was not only right, it was new."

Article reprinted from GW Magazine/Spring 2000, p.14